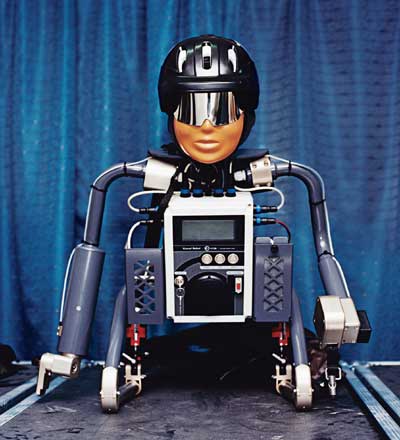

Robot camel jockeys. That’s about half of what you need to know. Robots, designed in Switzerland, riding camels in the Arabian desert. Camel jockey robots, about 2 feet high, with a right hand to bear the whip and a left hand to pull the reins. Thirty-five pounds of aluminum and plastic, a 400-MHz processor running Linux and communicating at 2.4 GHz; GPS-enabled, heart rate-monitoring (the camel’s heart, that is) robots. Mounted on tall, gangly blond animals, bouncing along in the sandy wastelands outside Doha, Qatar, in the 112-degree heat, with dozens of follow-cars behind them. I have seen them with my own eyes. And the other half of the story: Every robot camel jockey bopping along on its improbable mount means one Sudanese boy freed from slavery and sent home.

It’s July in Qatar, one of the hottest months in one of the hottest places in the world, and in an air-conditioned double-wide that sits baking in the sun, there are two experiments going on. One to see if the robots themselves will work, and one, less explicit, to measure the reach and touch of technology. It’s a moment created by rampantly colliding contexts: Western R&D, international NGO pressures, Arabian traditions, petroleum wealth, and benevolent despotism. If it works, the result will be both simple and powerful (one small step for robotics, one giant leap for social progress): The standard modernist gambit of taking a crappy job and making it more bearable through mechanization will be transformed into a 21st-century policy of taking appalling and involuntary servitude and eliminating it through high tech. Everybody will win a little. The children will be set free, the owners will get to keep their pastime, the US State Department will consider it a good start, and the camels will continue to do their camel thing.

So here comes Alexandre Colot, project and services manager for K-Team, the Swiss company that designed the robots. He pulls his black Lexus SUV into a tiny, sand-swept town called Shahaniya, which consists of a few stall-sized shops surrounded by camel farms, encircled by long, narrow tracks where the races are run. It is the off-season and there are few people around: a handful of Sudanese farmers napping in their pickups at a crossroads, a half dozen Bedouin stable boys in long white robes and head scarves hanging around the parking lot. Colot steps out into the heat, an unlikely figure for an emancipator – not because he lacks charisma, or even soulfulness, but only because he is, well, Swiss. Quiet, industrious, patient, and organized. He and his crew park outside the trailer and begin to unload their cargo. There they are: dozens of steel cases holding robots, remote controls, saddles, and spare parts.

Qatar is one of those odd countries that only late capitalism could have created. It’s a little thumb of land that sticks out from Saudi Arabia into the Persian Gulf, and like many states in the region, it sits on an enormous pool of fossil fuel – in Qatar’s case, natural gas. But unlike some of its neighbors, it’s Western-friendly – there’s a US Air Force base down the road from Doha – and the current emir, who’s ruled the country since he deposed his father in a bloodless coup in 1995, has been engineering an Arab perestroika. Al Jazeera is based here; the emir created it by decree. Islamic law coexists with civil codes, and fundamentalists are relatively few. Some women are fully veiled, some wear Western dress, and no one seems to mind much either way. There are Bedouin with mobile phones, sheikhs in sunglasses driving SUVs. No liquor and no pork, but vast malls housing Starbucks and Cinnabon stores. Doha, the capital, looks as if half of it is being constructed and half of it is being torn down, and it’s impossible to tell which half is which.

But however modern the Qataris may be, some traditions linger. For thousands of years, camel racing has been the sport of kings throughout the Arab peninsula – Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates. A fast camel can cost several hundred thousand dollars, and an owner may house and feed scores of them. The closest American equivalent is not Thoroughbred racing but polo. There is no gambling or online casinos, though there are various prizes for the winners, and the sport is not the people’s choice (soccer is). There are few live spectators and no television cameras, just a narrow sandy track about 10 miles long, looping through the desert outside Doha, where every year from October to April, wealthy men gather to run camels against one another.

It is not, for all that, an entirely benign diversion. A camel will not run without someone riding it and egging it on. The lighter the jockey, the faster the camel. For as long as anyone can remember, the solution was to use child jockeys – not adolescents, but little boys as young as 4, hustled in from poorer countries like Sudan and kept in hovels in the desert where they did nothing but ride camels. They were denied even rudimentary schooling, they were starved to keep their weight down, and their injuries were often left untreated. In Qatar, there were a few hundred such children; in neighbouring UAE, which used Pakistani and Bangladeshi boys as well as Sudanese, there were as many as 3,000. Trainers would choose whoever was handy and ready, stick him up on a saddle behind the camel’s hump, and when the race started, bark orders through walkie-talkies the boys wore strapped to their chests.

So it was that the emir, Hamad Bin Khalifa Al-Thani, announced the replacement of all child jockeys with robots. The Qatar Scientific Club created a prototype but as one of their members said, “it was huge.” The search for a suitable robot was then assigned to the Qatar Industrial Development Bank. Requests for submissions went out to robotics corporations in the US, Europe, and Japan.

Alexandre Colot remembers receiving a slightly cryptic email in late 2003. He was working at K-Team headquarters outside Lausanne, Switzerland, when the query came: “Do you have robots that could be used in camel races to replace jockeys in Qatar?” K-Team is a small company that makes educational robots, mostly – machines that they sell to schools to give students hands-on experiences with them. A few years ago, the firm got some press when scientists from Georgia Tech connected one of their robots to live cultures from a rat’s brain; the resulting publicity brought them to the attention of the Qatari government.

The email request was unusual, to say the least, but K-Team made a bid (Colot won’t say how much it was), they were hired, they took a fact-finding trip down to Shahaniya, and they put together a team of 10 engineers, two zoologists, and a designer.

“There were three parts to the problem,” Colot says. “The first part was environmental parameters – the heat of the desert, for example. The second part was the races themselves. There are a lot of shocks that the unit had to be able to take. The camels travel at about 25 miles per hour. The third part was the interaction with the animal.”

Let us pause here, then, to pay homage to a camel named Hanoud: After each redesign, K-Team would travel back to Qatar and test various prototypes on her. “Without this camel, we would not be here today with everything finished,” says Colot. “She was really very, very quiet, so we could work with her for two hours, installing the saddle and everything, without her moving. She was really incredible.”

For their 10 grand, the Qataris will get an aluminum frame on shock absorbers, hinged arms, and, for a thorax, a box about the size of a hardcover book. Inside the box there’s a processor, four microcontrollers, and a soundboard. On the racetrack, trainers follow each camel in an SUV, wielding a remote. With a joystick and buttons they can maneuver the whip, striking the camel in front, on the side, or on its flank; control the force of the blow; and spin the whip so it whistles past its ear (a goading action known as khali). With a slider, they can tighten or lengthen the reins; a screen on the remote displays the camel’s speed and heart rate, and the life left in the battery.

Still, there are aspects of the design that only this project, in this culture, could inspire. The robot camel jockeys have plastic heads that wear wraparound sunglasses and bicycle helmets. Their features are vaguely childlike, and their skin is an odd orange color – part Swiss, part Arabic, and part Bedouin, or so it seems. Fair enough, but the heads are as empty as a department store dummy’s. There are no electronics in there: They exist only to anthropomorphize the robots to the point where the camels – skittish creatures – will accept them.

“When we first came down here with the robots,” Colot says, “they had white, white faces. Like ghosts. We put one on the back of the camel, but the camel took off in a U-turn, running in the wrong direction. That was when we realized how important it was to reduce stress on the camel.” By changing the color of the faces, they sought to assure the camels that these new riders were not so different from the previous ones.

An interesting problem: a simple solution. But Islam forbids representations of the human form: The robots could be considered graven images, inducements to idolatry. And while, as one trainer put it, “it’s not as if anyone is going to be tempted to worship these things,” the Saudis, who take such matters more seriously, are right next door and watching. The forms of the robot camel jockeys have been judged too close to statuary for comfort, and word has come down from the prime minister (he’s the emir’s brother – it’s that kind of country) that the faces have to be removed before racing season begins.

On this day in July, Colot waits patiently with his prototypes. The trainers are scheduled to arrive at 3 o’clock. But they’ve been somewhat reluctant to participate in this experiment, and when the time comes for the great unveiling, no one is quite sure what will happen. Three or four officers from the Qatar Industrial Development Bank stand around making small talk. A few owners drift into the trailer, linger for a while, drinking hot, sweet tea from Dixie cups, and then drift out again. The wind outside is so strong that it rocks the trailer and howls through the casements.

Late in the afternoon, the trainers show up, all at once: a dozen or so men in flowing white, bumping noses to greet each other, chattering, and then examining the robots, which are lined up in a row like obedient schoolchildren. Amid the Arabic being spoken, one can make out the lingua franca of the borderless world of tomorrow, today: joystick, laptop, robot, they say, and, oh, yeah – PlayStation. There’s a great deal of laughing, and one of the robots is picked up and passed around; some of the trainers cluck, some nod in admiration. Colot runs through the basics of the devices, and then suddenly the eminences appear: Sheikh Abdullah Bin Saud Al-Thani, a few visitors from the US embassy, a human rights worker. A demonstration is hastily arranged.

In the Catalog of the Improbable, this must be listed high: a camel named Zael, legs folded under him on the desert floor as a nomad affixes an expensive electronic mannequin to his back. Beside the track, dozens of wealthy Qataris wait impatiently in their SUVs. Colot, wielding the remote, joins his team in the lead car. A few last adjustments are made, and then the Bedouin leads the camel into a trot before letting it go. The robot’s whip swings down against the animal’s haunch, and off it runs, racing into the dusty yellow setting sun, the robot bobbling up and down on its back, yanking the reins and bringing down the stick: a strange ungainly homunculus, avatar of a brave new world.

The demo is a great success; afterward the trainers and owners laugh and smile, in that tentative way that comes when something new and strange looks like it’s actually going to work. “I think it’s a good idea,” a trainer named Jassim Al-Ali says, “but I hope it will be improved. We will see what will happen in the actual race. I am concerned about the strength of the hit, and the weight of the robot. But I feel it will succeed, insh’Allah.” Indeed, when racing season starts a few months from now, all of the jockeys will be robots. Soon Qataris will explain to their children that once, long ago, as bizarre and benighted as it may sound, human jockeys used to ride the racing camels.

It would be nice to end the story here, with technology triumphant, but there’s more to say. Because, as far as human rights go, the robot camel jockeys are having a mixed effect, as such programs often do. They were meant to help free the children, but freedom is not simple. The State Department was pushing the Qatari government to set up a repatriation program with compounds and rehabilitation centers, but the Qataris simply started shipping the children back to the Sudan, which these days must qualify as one of the world’s worst places to be. None remain to testify to what they’ve been through. “There are no babies here,” one stable hand says, referring to the child slaves. But the compound he runs – bleak, hot, and silent – bears the signs of their having once been there, in the form of a rusty swing set at one end of an otherwise empty courtyard.

In effect they have simply been sent from one circle of hell to another. As Ali al Mohanadi, a camel owner and a colonel in the Qatari Amiri air force, says to me, “If you get them out of this job, are you going to improve their life? No. They will go to their death. They will go to the Sudan and live there as they did before, with no education, no food, nothing. How bad will their life be there? Nobody cares about it.”

Feleke Assefa, from the State Department’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, explains that the children were sent back to the Sudan without so much as a medical checkup, let alone basic lessons in how to read and write. Still, it’s a step in the right direction. “These children were slaves,” he says. “You can’t argue that slavery is better than freedom.” And he’s right, of course: You can’t. But you can argue that progress unaccompanied by a keen ear for context is just a game of Whack-a-Mole. You pound out one problem and another appears right next to it.

All the children are gone, but there are some young men hanging about, former child jockeys now old enough to stay on as stable hands. Abdullah is one: Thin, windburned, and slightly forlorn, he came from the Sudan in 1994 at the age of six. “When I was small I rode the camels,” he recalls. “But now, no. Any job, I can do it. I want to stay here, but when the robot came in there was no job for me.” We were surrounded by wealthy owners and trainers, and he seemed anxious to put a good face on things. “It is OK for us,” he said suddenly. “No problem. The robots, they are very good.”

As good as him?

He laughed a little uncomfortably. “If they could understand Arabic, they would be as good as me,” he says.

“We’re working on a voice recognition system,” Alexandre Colot tells me later. “It’s a direct request from the prime minister.”

Jim Lewis (jlewis99) wrote about in issue 11.02.

Trainers, who follow the racing camels in SUVs, guide the mechanical jockeys by remote control. Andrew Hetherington

Trainers, who follow the racing camels in SUVs, guide the mechanical jockeys by remote control. Andrew Hetherington

The robots are lifelike enough to reassure the camels. But some worry they’re too lifelike, inducements to idolatry. Andrew Hetherington

Alexandre Colot is project manager for the Swiss company that’s selling dozens of camel jockey robots to Qatar. Andrew Hetherington

The robots fit into specially designed saddles that sit behind a camel’s hump. Andrew Hetherington

Qatari officials spent the summer preparing for the switch from humans to robots. Andrew Hetherington

“When the robot came in there was no job for me,” says one former child jockey who now works as a stable hand. Andrew Hetherington

The original article was published on wired.com

Last Updated on April 29, 2025

Salem Mubarak Al-Sheydani

Salem Mubarak Al-Sheydani is a respected expert in online casinos and betting, with over 10 years of industry experience. As the exclusive reviewer for uae-onlinecasinos.com, he combines deep local insight with hands-on knowledge as a seasoned player. His reviews are known for their honesty, clarity, and focus on responsible gaming.